Part IV of a five-part series on Italy’s grain battles

As Italy declared its vittoria sul grano, something in the wheat department was brewing across the Atlantic. Norman Borlaug took a keen interest in Nazareno Strampelli’s work and led initiatives to increase agricultural production worldwide. Borlaug made quick progress. After all, in the 30 years separating Mussolini’s battaglia del grano and Borlaug’s Green Revolution, hybridised seeds, modern management techniques as well as synthetic fertilizers and pesticides had become more familiar terms.

Through innovations including developing rust-resistant wheat varieties that increased yield by 20% to 40%, semi-dwarf wheat varieties that could withstand strong winds and hold up huge loads of grains, and a technique known as “shuttle breeding” to speed up the breeding process by having two harvests per year in different climatic conditions, Borlaug transformed the developing world’s ability to feed its population. He received the Nobel Peace prize in 1970 for “preventing malnutrition, famine and the premature death of hundreds of millions”.

Norman Borlaug (Source)

The Green Revolution achieved its aim of alleviating hunger in countries like India, China and Mexico. However, it also provoked a shift in diets as more and more people turn to wheat as a staple. While its single-minded focus had served a very specific problem extremely well, the Green Revolution failed to anticipate unintended consequences on human nutrition.

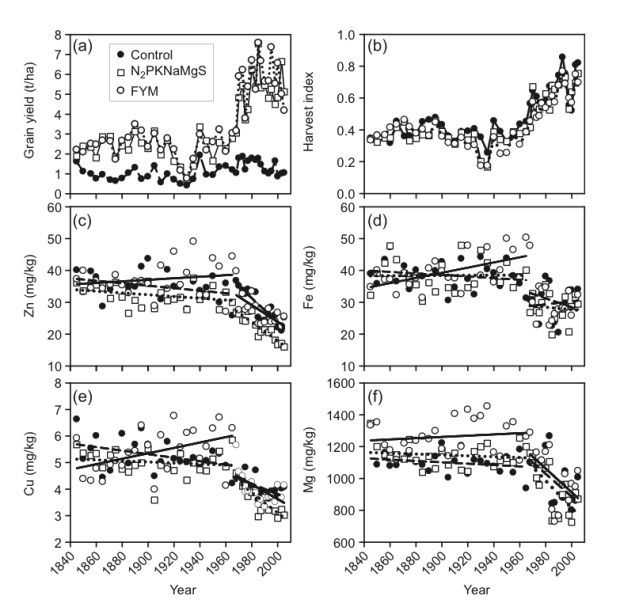

Results from the Broadbalk Wheat Experiment, that has analysed grains’ nutrient composition since 1843, show that the mineral content in grains remained stable up till the mid-60s, then decreased significantly with the introduction of semi-dwarf, high-yielding varieties. In addition, increasing yield was found to be a key factor that explained the downward trend in grain mineral concentration.

Graph tracking grain yield and grain mineral density from 1840 to 2000 (Source)

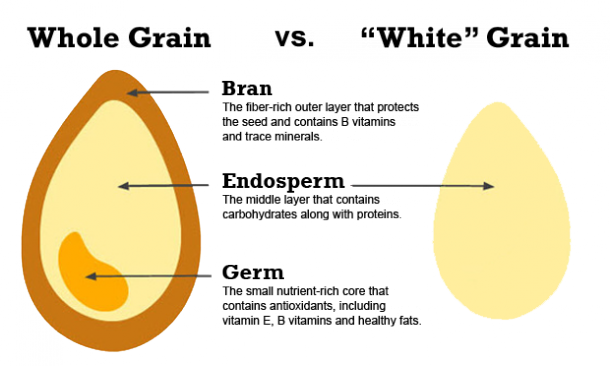

The double whammy of highly industrialised wheat processing further strips grains of all their goodness. Cheap and efficient, steel roller mills manage to isolate the starchy endosperm (the middle layer of the grain) and churn out soft, light, white flour that ships and stores better – while eliminating, ironically, the portions that account for over 25% of a grain’s protein and that are richest in fibre, vitamins, unsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants and minerals. The resulting flour is therefore heavily tipped towards refined carbohydrates that act like a sugar in the body.

Nutritional differences between whole and refined grains (Source)

Subsequent grain breeding have also catered to the incessant demands of industrialised milling and bread manufacturing by increasing protein and gluten strength – these make flours easier to handle, especially with the aid of heavy machinery. The exact cause of the spike in gluten-related intolerances has not been pinpointed yet, and we stop short of naming modern wheat varieties as the culprit. Nevertheless, ancient grain varieties, with their gut-friendly weak gluten, processed in accordance with loving and ethical methods, definitely offer a plethora of benefits and reassurances over their younger counterparts.

So we should turn to Ugo de Cillis, whose crusade to improve wheat agriculture in Sicily consisted in systematically replanting local, autochthonous varieties? Why aren’t these varieties more widely available?

Part V: Coldiretti’s Battaglia del Grano

References

http://www.forbes.com/sites/henrymiller/2012/01/18/norman-borlaug-the-genius-behind-the-green-revolution/#1e117fe9415b

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Revolution

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19013359

http://wholegrainscouncil.org/what-whole-grain

https://experiencelife.com/article/the-truth-about-refined-grains/

http://ansonmills.com/grain_notes/14